「二十四孝図 ふしぎで過激な親孝行」展の開催期間中、阿品駅⇔海の見える杜美術館無料送迎バスを運行します。

どうぞご利用ください。

さち

「二十四孝図 ふしぎで過激な親孝行」展の開催期間中、阿品駅⇔海の見える杜美術館無料送迎バスを運行します。

どうぞご利用ください。

さち

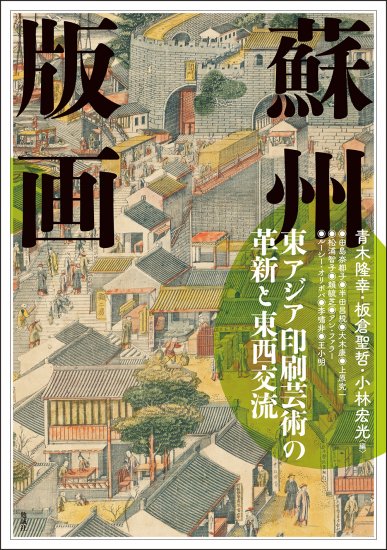

昨年の展覧会「蘇州版画の光芒―国際都市に華ひらいた民衆芸術―」の記念講演会「中国版画研究の現在」の発表を軸に構成された論文集、『蘇州版画 東アジア印刷芸術の革新と東西交流』が勉誠社から出版されます。

以下出版社HPより

芸術文化の古い歴史を持ち、経済的繁栄をきわめていた17、18世紀の中国・蘇州市に生まれた「蘇州版画」。

吉祥的な画題のみならず、教訓、歴史故事、名所旧跡、通俗文学や詩の絵解きなどさまざまな題材をとり上げ、当時の都市のにぎわい、市民の暮らしぶりを大きな画面に描き伝える貴重な視覚資料でもある。

技法も多彩で、濃淡の墨摺にはじまり、複数色の色刷り、さらに手彩色によって色数を増やし、また、舶載された西洋銅版画などの陰影法や透視図法も積極的に応用する。

これらの蘇州版画は、江戸時代には長崎に大量にもたらされ、ヨーロッパにも輸出されて宮殿の室内を飾り、美術工芸品への応用が注目されてきた。

近年新たな発見や蒐集が進み、内外で学際的な関心の対象として注目を集めている蘇州版画。

中国版画史を突出して彩るその歴史と世界的広がりを、国内外の第一線の論者が多数の図版を交えて明らかにする貴重な一書。

予約販売が始まっていますので、ご興味のある方は是非お申し込みください。

蘇州版画 [978-4-585-32541-3] – 3,520円 : 株式会社勉誠社 : BENSEI.JP

さち

さてこのたび、2023年5月27日・28日に行いました「蘇州版画の光芒 国際都市に華ひらいた民衆芸術」記念講演会:「中国版画研究の現在」の全講演をYouTubeにアップしました。

どうぞご興味ある講演に下のリンクからお入りください。

さち

Technique as a Cultural Form: Making “Xiyang” in Suzhou Prints

Yu-chih LAI

Academia Sinica

作为文化形式的技术:苏州版画中的“ 西洋”塑造

赖毓芝

中央研究

文化形式としての技法:蘇州版画における「西洋」の制作について

賴毓芝

中央研究院

Exploring the Jesuit Role in Early Qing Suzhou Prints

Anita Xiaoming WANG

Birmingham City University

探讨清初苏州版画中耶稣会所发挥之作用

Anita Xiaoming WANG

伯明翰城市大学

清初期の蘇州版画におけるイエズス会の役割についての考察

アニータ・シャオミン・ワン

バーミンガム・シティ大学

Investigating the Origins of Eighteenth-century “Still-life” Prints in Painting

Anne FARRER

Sotheby’s Institute of Art – London,Center for Chinese Visual Studies, China Academy of Art, Hangzhou,and Muban Educational Trust

自绘画中探查十八世纪“静物画”版画之起源

Anne FARRER

伦敦苏富比艺术学院,中国美术学院・杭州,木版教育信托

18世紀の「静物画」版画の起源を絵画で探る

アン・ファーラー

サザビーズ美術カレッジ・ロンドン、中国美術学院・杭州、木版教育基金

Western Palaces and Suzhou Prints

Lucie OLIVOVA

Masaryk University

西方宫殿与苏州版画

Lucie OLIVOVA

马萨里克大学

西洋宮殿と蘇州版画

ルーシー・オリボバ

マサリク大学

Chinese Prints in Leykam Room

XiaoFei LI

Chinese National Academy of Arts

关于莱凯厅中国版画

李啸非

中国艺术研究院

レイカムの間の中国版画

李嘯非

中国芸術研究院

Single-sheet Prints of the Northern Song Dynasty and the Beginnings of Reproduction Pictures

Kobayashi Hiromitsu

Honorary Professor, Sophia University

北宋时期的单幅版画与复制画的开端

小林宏光

上智大学名誉教授

北宋時代の一枚摺版画と複製絵画のはじまり

小林宏光

上智大学名誉教授

Suzhou and Hangzhou – Looking at Suzhou Prints from the Development of Urban Imagery

Itakura Masaaki

Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia, Tokyo University

从城市图发展的观点所见的苏州版画─以苏州和杭州为例

板仓圣哲

东京大学东洋文化研究所

蘇州と杭州、都市図の展開から見た蘇州版画

板倉聖哲

東京大学東洋文化研究所

Literary Tales and Chinese Prints

Ōki Yasushi

Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia, University of Tokyo

故事与中国版画

大木康

东京大学东洋文化研究所

物語と中国版画

大木康

東京大学東洋文化研究所

Posters from the Republic of China as the Descendants of Chinese Prints — Centering on Succession and Changes in Tradition

Tajima Natsuko

Ome Municipal Museum of Art

民国时期海报里的中国版画复兴─以传统的继承与变化为中心

田岛奈都子

青梅市立美术馆

中国版画の末裔としての民国期ポスター~伝統の継承と変容を中心として~

田島奈都子

青梅市立美術館

The Transmission of Chinese Prints to Japan

Aoki Takayuki

Umi-Mori Art Museum

中国版画在日本的流传

青木隆幸

海杜美术馆

中国版画の日本伝来

青木隆幸

海の見える杜美術館

「蘇州版画の光芒 国際都市に華ひらいた民衆芸術」記念講演会:「中国版画研究の現在」のプログラムのうち、以下の発表がYoutubeに日英中3か国語で公開されたことをお知らせいたします。

【日本語】

「物語と中国版画」

大木康

東京大学東洋文化研究所

蘇州版画も含めて、画像の背後には、物語があるということも可能である。例えば、桃や石榴は多産、多子の象徴であるが、それらを描いた図があれば、それはそうしたことへの願いが込められているわけである。関羽の肖像画などは神像としての意味があるが、やはり背後に『三国志演義』の関羽の物語が思い浮かべられるであろう。孟母三遷などの故事の図柄にしても、その背景に物語がある。だがここでは、より直接的に小説や戯曲の物語に関わる蘇州版画について考えてみたい。

小説戯曲に関わる版画には、物語のハイライトの一場面を切り取って描いた図と、物語のいくつかの場面を連環画式に描いたものとがある。そして、物語の場面の少なからざるものは、芝居の衣装を着た人物の舞台上の様子を再現したものである。これらの芝居絵は、いったい何のために、どのような人を対象に作られたのであろうか。小説戯曲と版画については、小説戯曲の書物の挿絵としての版画が問題にされることが多いが、一方で、一枚物の版画も数多く存在する、その意味についても考えてみたい。

【英語】

Literary Tales and Chinese Prints

Ōki Yasushi

Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia, University of Tokyo

It is possible that there is a story behind any image, which is also the case for Suzhou prints. For example, peaches and pomegranates are symbols of an abundance of children, and images that contain them also express that desire. Portraits of Guan Yu portray him as a deity, but surely, they are also intended to remind viewers of the stories of Guan Yu from the

Romance of the Three Kingdoms. There are also stories behind images of historical figures and events, such as found in “The Importance of Raising Children in a Good Environment”. Here, however, I would like to consider Suzhou prints that are more directly associated with literary tales from novels and the Chinese opera.

Some of these prints illustrate highlights of the tales with individual scenes, while others link multiple scenes together through the imagery. A considerable number of scenes are also recreated by figures on stage wearing costumes. Why were these pictures of dramatic plays created, and what kind of people were they made for? When it comes to the relationship between novels, Chinese opera, and prints, the question of prints made as illustrations for books is often considered, but here I would like to think about the meaning behind the existence of the great many single-sheet prints that remain with us today.

【中国語】

「故事与中国版画」

大木康

东京大学东洋文化研究所

包括苏州版画在内的所有图像背后,很可能都有一个故事。比如说,桃子和石榴是多产和子孙满堂的象征,所以如果看到描绘它们的图像,就可以推测其中含有这一类祝愿的意图。又比如说,一幅关羽的画像固然可以看作是神像,但同时也让人很难不联想到《三国演义》中关羽的故事。甚至像孟母三迁一类典故的图,它的画面设计背后也有一个故事。不过,在这场演讲,我想探讨和小说戏曲的故事直接相关的苏州版画。

与小说戏曲相关的版画可以分为两种类型:一种是截取并描绘故事中最精彩场面的单一场景,另一种是以一系列的连环画面来描绘故事中的复数场景。此外,不少表现故事中场景的版画,是重现了戏装的人物登台演出的舞台场面。这些戏曲画究竟是为何而作,又是为谁而作的呢? 在探讨小说戏曲与版画的关系之际,小说戏曲这类书籍的版画插图向来引起比较多的关注,但其实也有不少以小说戏曲为主题的单幅版画作品存世,在此我想探讨一下它们所代表的意义。

さち

「蘇州版画の光芒 国際都市に華ひらいた民衆芸術」記念講演会:「中国版画研究の現在」のプログラムのうち、以下の発表がYoutubeに日英中3か国語で公開されたことをお知らせいたします。

【日本語】

「レイカムの間の中国版画」

李嘯非

中国芸術研究院

本講演では、オーストリア・グラーツ宮殿美術館のレイカムの間(Leykam Room)にある中国木版画28枚に焦点を当てる。これら製作技術と視覚効果が共に見事である版画は7つのテーマによって構成される。その画面に描かれた人物の表情、髪型と衣装は、清朝初期の社会で流行ったイメージと密接に関連している。それに広く使われていた線遠近法、キアロスクーロ、ハッチングといった西洋の芸術的要素は、18世紀の姑蘇版画の顕著な特徴でもある。またその光影や立体感の表現は、清初期の宮廷芸術における、ヨーロッパの宣教師から伝わった銅版画や絵画、建築装飾などの表現にも類似する。レイカムの間の木版画は、18世紀前半に蘇州で制作された可能性が高いと思われる。その縁起の良さと文人趣味を意図的に強調する表現も、当時の消費者の好みに合わせたものであろう。世界貿易の発展とともに、18世紀はヨーロッパでロココが流行し、思想や技術、物質が交流した時代である。いわゆる「シノワズリ」(Chinoiserie)は、17世紀から18世紀にかけてのヨーロッパ文化に最も頻繁に登場した要素の一つであり、中国版画が持つ物質性と視覚性の特徴を生かした多様な物質的形態を含んでいる。

【英語】

Chinese Prints in Leykam Room

XiaoFei LI

Chinese National Academy of Arts

The subject of this lecture is twenty-eight sheets of Chinese woodcuts in Leykam Room in Palace Museum Graz, Austria. Seven topics constituted those prints in which manufacturing technique and visual effect were both spectacular. Facial expression, hairstyle, and costume, the feature of figures in the woodcuts were related closely with popular images in Early Qing society. And what was more, western artistic elements, for example, linear perspective, chiaroscuro, and hatching, were widely utilized in those woodcuts, that were also distinctive characteristic of Gusu prints in the 18th century. Expression of light shade and three-dimensional similarly appeared in earlier court arts such as copperplate engraving, painting, and architectural ornament which originated from European missionaries. Highly possibly the woodcuts in Leykam Room were produced in Suzhou in the first half of 18th century. Pursuit of auspiciousness and literati taste were intentionally highlighted and thus fitted consumers. With developing world trade line, the 18th century was the time of Rococo in Europe, exchanging of idea, technique and material. So-called “Chinoiserie” was one of the most frequent element in European culture from the 17th to the 18th century, including diverse material forms in which Chinese prints has the characteristics of materiality and visuality.

【中国語】

关于莱凯厅中国版画

李啸非

中国艺术研究院

本演讲聚焦于奧地利格拉茲宮殿美術館莱凯厅(Leykam Room)中的28幅中国木刻版画,这些制造技术与视觉效果均十分出色的版画由7个主题所构成,画中人物的脸部表情,发型,服饰等特征都与清初社会流行的图像密切相关。更重要的是,这些木刻版画与十八世纪姑苏版画的显著特征一致,两者均广泛运用了西方的艺术元素,如:线性透视法,明暗对比法和阴影线等等。此外,清初的宫廷艺术作品中与莱凯厅木刻版画类似的光影,立体表现,在通过欧洲传教士传入的铜版雕刻,绘画和建筑装饰中均可得见。莱凯厅木刻版画很可能制作于十八世纪上半叶的苏州,且显然为了迎合当时的消费者喜好,图像刻意强调了祈求吉祥,彰显文人素养的表现。随着全球贸易路线的发展,十八世纪的欧洲洛可可时期,是一个各种思想,技术和物质频繁交流的时代。当时一般所称的“中国风(Chinoiserie)”,是十七至十八世纪欧洲文化中最常见的元素之一,而中国版画所具有的物质性和视觉性特征也包含在这些形成“中国风”的多元物质形式之中。

さち

「蘇州版画の光芒 国際都市に華ひらいた民衆芸術」記念講演会:「中国版画研究の現在」のプログラムのうち、以下の発表がYoutubeに日英中3か国語で公開されたことをお知らせいたします。

【日本語】

西洋宮殿と蘇州版画

ルーシー・オリボバ

マサリク大学

東西の海上貿易の発達に伴い、中国からさまざまな高級品がヨーロッパにもたらされた。その中に、数は多くないが、18世紀前半に蘇州で制作された一枚摺の木版画があった。「高級品」として見るに値するかどうかは文化の盗用(cultural appropriation)の問題に関わるものの、少なくとも当時のヨーロッパではそれを高級品と見なされていた。現在でもヨーロッパのコレクションには多様な蘇州版画が存在しており、多くの専門家の関心を集めている。本講演では、蘇州版画が壁紙として室内装飾に使用された中欧の宮殿について、これまで語られてきたもの、またこれまで知られていなかったものを紹介する。厳選した事例を通し、現地のデザイナーが、非常に薄い紙でできる、壁紙に適していない小さい判型をする版画にどう対処したかを説明する。蘇州版画という「エキゾチックな」要素をどのようにロココ調の部屋に取り入れられるかのは、インテリアデザインの変化し続ける流行に新しい空想的な道を開いており、また実際に蘇州版画はロココ様式の特徴の一部として受け入れられるようになった。ヨーロッパ史における蘇州のグラフィックアートの特異な痕跡は、1757年以降、新たに行われた広東システムという貿易管理体制の影響により、その姿を消した。

【英語】

Western Palaces and Suzhou Prints

Lucie OLIVOVA

Masaryk University

With the development of maritime trade between East and West, a wide range of luxury commodities from China arrived to European market. Among them, although not in huge numbers, were single sheet woodblock prints crafted in Suzhou in the first half of the 18th century. Whether or not they deserved to be seen as ‘luxurious’ was a matter of cultural appropriation; at the time Europeans considered them as such. A diversity of Suzhou prints can be seen in European collections even now, and they increasingly attract specialists’ attention. My presentation will introduce some previously recounted, as well as hitherto unknown palaces in Central Europe where Suzhou prints were used for interior decorations, often as wallpapers. Employing selected examples, I shall describe how local designers dealt with the challenges resuming from the uncommonly thin paper, or the unsuitably small format of the prints. The changing fashion of interior design gradually opened new fanciful

ways of how to incorporate the ‘exotic‘ components into a rococo room, and indeed, make them one part of rococo features. The singular trace of Suzhou graphic art in European history ended after 1757, as a consequence of the newly introduced Cantonese system.

【中国語】

西方宫殿与苏州版画

Lucie OLIVOVA

马萨里克大学

随着东西海上贸易的发展,大量来自中国的奢侈品进入了欧洲市场。其中,尽管数量不多,一批十八世纪上半叶在苏州制作的单幅木刻版画也随之流入欧洲─虽然它们是否值得被视为“奢侈品”是一个牵涉到文化挪用(cultural appropriation)的问题,但至少当时的欧洲人是如此认为的。即使是现在,在欧洲的收藏中仍可以看到各种各样的苏州版画,目前也有越来越多的专家学者注意到它们的存在。本演讲将介绍苏州版画在中欧地区宫殿空间内的运用情形:这些空间有些曾在先行研究中登场,有些则迄今尚未为世人所知。苏州版画在这些宫殿空间中被用于室内装饰─通常是作为墙纸使用。我将会通过所选案例,向各位说明当地设计师如何应对这些纸张异常轻薄,版型对墙纸来说过小的苏州版画所带来的挑战。通过将苏州版画这类“异国情调的”成分融入洛可可风格的室内空间,变化多端的室内设计时尚吹起了一股奇特的崭新风潮,而实际上这些苏州版画也成为了洛可可风格特征的一部分。1757年以后,由于新推行的广东体系贸易特区管制所造成的影响,苏州版画在欧洲历史上留下的奇特轨迹就此画下句点。

さち

「蘇州版画の光芒 国際都市に華ひらいた民衆芸術」記念講演会:「中国版画研究の現在」のプログラムのうち、以下の発表がYoutubeに日英中3か国語で公開されたことをお知らせいたします。

【日本語】

清初期の蘇州版画におけるイエズス会の役割についての考察

アニータ・シャオミン・ワン

バーミンガム・シティ大学

西暦1700年頃、明らかにヨーロッパの影響を受けた蘇州版画が登場した。当時、蘇州版画は中国製品としてヨーロッパと日本で人気を博していた。ところが、その生産時期が1700年代から1760年代にまでという短い期間しか続いておらず、その出現と消滅は、中国におけるカトリックと関係していた。すでに述べたように、このような蘇州版画の中には、ヨーロッパの絵画技法、とりわけ線遠近法、陰影法、ハッチングが使われる。現在、日本が所蔵する蘇州版画の中には、これらの技法がすべて盛り込まれているものもあり、更にその中には、ヨーロッパからの影響の源を直接示す題が刻まれているものもある。ヨーロッパからの影響がどのようにしてこれらの版画に取り入れられたかについては、これまでにも議論があった。講演者は、18世紀の蘇州の版画にヨーロッパの絵画技法が流用と模写されたのは、複数の手段による可能性が高い説に賛同する。しかし講演者はここで、ヨーロッパの絵画技法の導入に関しては、イエズス会が最も重要な影響源であったと主張したい。文書記録によれば、イエズス会は、最も早い時期に直線遠近法やその他のヨーロッパの絵画技法を用いたと知られる蘇州の版画家たちとつながり、場合によっては友人関係となったことがあるという。本講演では、蘇州の版画における線遠近法やその他の西洋の芸術技法の出現が、どのように中国におけるイエズス会の存在と密接に関係していたかを論じ、またその後の18世紀半ばに、版画におけるヨーロッパの絵画技法の使用が減少したことへの可能的な影響要因について分析する。

【英語】

Exploring the Jesuit Role in Early Qing SuzhouPrints

Anita Xiaoming WANG

Birmingham City University

Around 1700, Suzhou woodblock prints appeared with a clear Europeaninfluence.They became popular Chinese products in Europe and Japan. However, they were only produced for a short period of time, roughly from the 1700s to 1760s, and their emergence and disappearance was related to Catholicism in China. As already note, certain Suzhou prints made use of European pictorial techniques, most notably linear perspective, shading, and hatching. A number of Suzhou prints now in Japanese collections feature all of these techniques, some of which bear inscriptions which point directly to their European sources of influence. There has been debate about how these influences came to be in these prints. I accept that the appropriation and transfer of European pictorial techniques into eighteenth century Suzhou printmaking most likely came about through multiple means. I argue however that the Jesuits were the primary source of influence with respect to the introduction of European pictorial techniques. There are documentary records indicating that Jesuits had connections with, and in some cases friendships with the earliest known Suzhou printmakers to use linear perspective and other European pictorial techniques. The presentation will discuss how appearance of linear perspective and other western artistic techniques in Suzhou printmaking was closely related to the presence of the Jesuits in China and analyse the possible impact on the later decline in the use of European pictorial techniques in prints in the mid-eighteenth century.

【中国語】

「探讨清初苏州版画中耶稣会所发挥之作用」

Anita Xiaoming WANG

伯明翰城市大学

西元1700年前后,苏州版画中开始出现了明显的欧洲影响。此时苏州版画已经是在欧洲和日本都相当受到欢迎的一类中国产品,然而这些版画的生产时期却为时极短,大致只持续了从1700年代至1760年代之间的这段时期,且它们的出现和消失都与天主教在中国的传播有关。如前所述,这些苏州版画使用了欧洲的绘画技巧,其中最显著的是线性透视,阴影,以及阴影线的运用。目前已知有一批现藏于日本的苏州版画中同时使用了上述所有技法,其中更有一些作品直接在标题中明示其欧洲影响的来源。关于这些欧洲影响进入苏州版画的途径,一直以来学界的意见都有些分歧。部分意见指出这些欧洲绘画技巧应是透过复数途径而被挪用和转用到十八世纪苏州版画之中的,我也同意这一说法。但在此我想强调:耶稣会士是引进欧洲绘画技巧至苏州版画的最主要影响来源。有文献记录表明,耶稣会士曾和最早开始运用线性透视法及其他欧洲绘画技法的苏州版画家有所交流,甚至在有些案例表明双方之间是有友谊存在的。本演讲将讨论苏州版画中的线性透视法和其他西洋艺术技法的出现如何与耶稣会士在中国的活动密切相关,并分析造成日后十八世纪中叶苏州版画中欧洲绘画技巧的使用频率降低的因素。

さち

「蘇州版画の光芒 国際都市に華ひらいた民衆芸術」記念講演会:「中国版画研究の現在」のプログラムのうち、以下の発表がYoutubeに日英中3か国語で公開されたことをお知らせいたします。

【日本語】

文化形式としての技法:

蘇州版画における「西洋」の制作について

賴毓芝

中央研究院

蘇州の版画にヨーロッパの影響があることは、議論の余地のない、よく知られた現象である。しかし、「ヨーロッパさ」の意味や、「西洋」か「泰西」(いずれも西洋を指す)様式とともに、どのように認識、選択、形成、再構築、表現されたかには、まだ議論の余地がある。このような一見自明な疑問に対する直接的な答えは、線遠近法の利用や陰影とモデリング技法の使用などである。これらの回答は真実であるが、ヨーロッパと中国の間の複雑なトランスカルチャー(trans-culturation)のプロセスを無視してはならない。そこで本講演では、「仿泰西筆法」(泰西の筆法を倣う)「仿西洋筆意」(西洋の筆意を倣う)など、いわゆるヨーロッパ様式を直接的に模倣し、または手本にしたことを示す題のある蘇州版画を出発点として、その中におけるヨーロッパさがどのように定義と形成されていたかを分析することにした。さらに、これらの蘇州版画は、ヨーロッパの視覚文化を伝えるもう一つの重要な拠点であった当時の清の宮廷で制作された中西折衷様式の絵画とは、どのように違ったかを解説する。最後に、本講演では、蘇州版画における「西洋」か「泰西」というのは、単なる新しい視覚効果の出現ではなく、「制作」ための新しい技法と提示する。また、その蘇州版画に求められる異国さは、ヨーロッパ憧憬を積極的に探求する重要なメディアである絵画に求められる異国さとは著しく異なったことを明らかにする。

【英語】

Technique as a Cultural Form: Making “Xiyang”

in Suzhou Prints

Yu-chih LAI

Academia Sinica

The European influence on Suzhou prints is an indisputable and wellrecognized phenomenon. But meanings of “European-ness” and how hey along with those of “Xiyang” or “Taixi” (both terms referring to the West) style were perceived, selected, framed, reconstructed, and represented remain up for debate. Immediate answers to this seemingly

self-evident question include the application of a linear perspective, use of shadowing and modeling, etc., and while these answers hold truth, one should not overlook the complex trans-culturation processes between Europe and China. The present paper thus takes Suzhou prints with inscriptions indicating their direct imitation or emulation of a so-called European style, such as “in imitation of the brushwork of Taixi”, “in imitation of the tone of Xiyang”, etc., as a starting point to analyze which characteristics of European-ness were defined and framed within the prints. In addition, how they differed from paintings in the European-Chinese eclectic style produced by the court of the time, another important center of transmitted European visual culture, is expounded. This paper then ultimately argues that it is not merely the manifestation of new visual effects, but the new techniques employed in “making,” that denote the desired foreign-ness in the prints, which is remarkably different from the case of painting which stands as another important medium that actively explores European aspirations.

【中国語】

作为文化形式的技术:苏州版画中的“ 西洋”塑造

赖毓芝

中央研究院

苏州版画中来自欧洲的影响是一个不容置疑的公认现象。然而,有关“欧洲性”的含义以及其与“西洋”或“泰西”(两者均指西方国家)风格如何被感知、选择、建立、重构和表现等问题,则仍有待讨论。对于这类看似不言自明的问题,直接的解答包括线性透视的应用、阴影和立体感的表现等等。然而,虽然这些解答所言不虚,但我们不应忽视欧洲与中国之间复杂的跨文化(trans-culturation)过程。因此,本演讲首先聚焦于苏州版画中一类在标题中指出其直接模仿或参考自当时一般认为的欧洲风格的作品─如以“仿泰西笔法”,“仿西洋笔意”等为题之作,分析这些版画中所定义和建构的欧洲性特征究竟为何。此外,当时的清代宫廷制作了许多兼容欧洲与中国两种风格的绘画,亦为另一个重要的欧洲视觉文化传播中心,本演讲也将论述上述苏州版画与当时宫廷绘画的相异之处。最后,本演讲将提示的是:苏州版画中的“西洋”或“泰西”,不仅仅是一种崭新视觉效果的表现,更是一种应用于“塑造”的新技术,它体现了人们期待版画应具备的异国情调;而绘画作为另一种积极探索对欧洲之向往的重要媒介,其对于异国情调的表现与苏州版画有着非常明显的差异。

さち

「蘇州版画の光芒 国際都市に華ひらいた民衆芸術」記念講演会:「中国版画研究の現在」のプログラムのうち、以下の発表がYoutubeに日英中3か国語で公開されたことをお知らせいたします。

【日本語】

中国版画の末裔としての民国期ポスター

~伝統の継承と変容を中心として~

田島奈都子

青梅市立美術館

洋紙に多色石版印刷術を用いて製作される近代ポスターの歴史は、中国においては清朝末期に、香港や上海に進出した外資系企業が用いたことによって始まる。初期の外資系企業によるポスターには、中国版画において人気の画題が、そのまま用いられることが多かった。しかし、民国期に入り中国の民族資本企業が国内に起こると、彼らは同時代風俗を主題とすることを好み、特に女性たちは最先端の衣装や髪型で描かれた。ところが1930年代に入り、満洲国の建国との関係から、中国国内における愛国的な運動がさらに活発化すると、それらはポスター図案にも影響を与えた。事実、これ以降の時代においては、中国版画と重なる伝統的な画題や風俗を主題としたポスターも盛んに製作され、満洲国皇帝・溥儀の即位に際して製作された一連の作品の中にも、そのようなものが存在している。なお、外国にも流布した伝統的な中国版画は、それゆえに描かれた図像を「中国」とする理解を西洋諸国に助長し、中国風に表現したい際の手本となった。

【英語】

Posters from the Republic of China as the Descendants of Chinese Prints — Centering on Succession and Changes in Tradition

Tajima Natsuko

Ome Municipal Museum of Art

The history of manufacturing modern, multi-color lithograph posters on Western-style paper began in China at the end of the Qing Dynasty, as they were used by foreign-owned enterprises that were expanding into Hong Kong and Shanghai at the time. In the posters of these early foreign companies, it was common to use themes that were popular in Chinese prints, just as they were in the past. However, entering the period of the Republic of China (1912–1949) as The development of national capital in the country, contemporary subjects are favored, particularly those depicting women in cutting-edge fashion with modern hairstyles. Entering the 1930s, the increase in nationalist movements had an influence on poster design. In later times, posters depicting traditional themes and customs that overlap with Chinese prints were frequently made, including those made to commemorate the ascension of the emperor of occupied Manchuria, Puyi (1906–1967). In addition, as traditional Chinese prints circulated outside of China, the images they depicted promoted an understanding of “China” in Western countries, becoming models for occasions when there was a desire to express something with a Chinese atmosphere.

【中国語】

民国时期海报里的中国版画复兴─以传统的继承与变化为中心

田岛奈都子

青梅市立美术馆

近代的海报印刷是以彩色石印技术在洋纸上印制而成,其在中国的历史始于清朝末年进驻香港,上海等地的外资企业所使用的印刷技术。早期外资企业制作的海报图案,大多照旧沿用传统版画的流行主题;其后随着民国时期中国民族企业在国内的崛起,民族企业的海报倾向以当代的风俗作为题材,尤其喜好描绘服装,发型引领时尚的女性形象。然而,1930年代国内爱国主义运动兴盛,其影响也遍及了海报设计。实际上,在接下来的时期,大量印制的海报主题多是回归中国版画传统的画题,或是描绘中国风俗,就连纪念伪满洲国皇帝溥仪登基时所制作的一系列海报之中,这类的主题也仍占有一席之地。此外,承袭传统表现的中国版画流传海外,也因此助长了西方国家认定其中图像即代表“中国”的风气,这些版画作品便成为海外艺术家表现中国式风格时所参考的范本。

さち

「蘇州版画の光芒 国際都市に華ひらいた民衆芸術」記念講演会:「中国版画研究の現在」のプログラムのうち、以下の発表がYoutubeに日英中3か国語で公開されたことをお知らせいたします。

【日本語】

「18世紀の「静物画」版画の起源を絵画で探る」

アン・ファーラー

サザビーズ美術カレッジ・ロンドン、中国美術学院・杭州、木版教育基金

本講演では、蘇州の丁氏工房制作、現在大英博物館所蔵の「静物画」4点(1906,1128,0.22–25)に焦点を当てる。これらの版画は、18世紀第2四半期にハンス・スローン卿(1660–1753)が収集した、「丁氏版画」(Ding prints)という通称を持つ合計29点の一枚摺セットに属される。最近の研究成果により、これらの一枚物は、従来考えられていた康熙帝時代(1661–1722年)ではなく、乾隆初期(1736–50年)に制作されたことが判明された。この4枚の版画には、花、古風な様式を持つ七宝焼の器、巻物、本、陶磁器、果物などが描かれており、現代の学者がそれをヨーロッパの命名法に基づいて「静物画」と分類した。本講演では、これらの版画の構図を以下の観点から考察する:(1)康熙朝の一枚摺版画の中の類似図像との関係、(2)季節の祝祭を祝うために描かれ、個人的な贈り物としてよく使われた「特別な場合のための」絵画のジャンルとの関連性、(3)清朝初期に中国に伝えられたヨーロッパの「静物画」類型図像との関連性。また、筆者の研究では、明末から清中期にかけて「静物画」版画における図像の構成、表現方法、意味合いがどのように変化していたかを明らかにすることも引き続いて解明する予定がある。

【English】

Investigating the Origins of Eighteenth-century “Still-life” Prints in Painting

Anne FARRER

Sotheby’s Institute of Art – London, Center for Chinese Visual Studies, China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, and Muban Educational Trust

This lecture will focus on four “still-life” prints from the Ding family workshops in Suzhou, now in the British Museum collection (1906,1128,0.22–25). These prints belong to a group of 29 single-sheet prints, referred to as the “Ding prints”, acquired by Sir Hans Sloane

(1660–1753) in the second quarter of the eighteenth century. Recent research has established that these single-sheet prints were made in the early Qianlong period (1736–50), rather than in the Kangxi period (1661–1722) as had previously been assumed. The images in these four prints include flowers, cloisonné vessels in archaistic form, scrolls,

books, ceramics and fruits, which scholars have categorised as “stilllife” compositions following European nomenclature. This lecture will investigate the compositions in these prints from a number of perspectives: (1) their relationship to similar images in single-sheet prints of the Kangxi period; (2) their connection with “functional” paintings made to mark seasonal festivities and often used as personal gifts; and (3) connections with images of European “still-life” genre introduced to China in the early Qing dynasty. It is intended that this study will also demonstrate how the image groupings, modes of representation, and

meaning embodied in the compositions changed through the late Ming to mid Qing dynasties.

【中国語】

「自绘画中探查十八世纪“静物画”版画之起源」

Anne FARRER

伦敦苏富比艺术学院,中国美术学院・杭州,木版教育信托

本演讲将聚焦于四幅由苏州丁家作坊制作,现由大英博物馆收藏的“静物画”版画(1906, 1128, 0.22–25)。这批版画属于汉斯·斯隆爵士(1660–1753)在十八世纪第二季度收购的一组通称为“丁氏版画(Ding prints)”的29幅单幅系列。近年研究结果显示,这组单幅版画应制作于乾隆初期(1736–50),而非以往所认为的康熙年间(1661–1722)。由于这四幅版画中的图像包括花卉,掐丝珐琅仿古器皿,卷轴,书籍,陶瓷和水果,现代学者便按照欧洲式的命名法将其归类为“静物画”作品。本演讲将从以下几个不同的角度来检视这批版画作品的构图:(1)它们与康熙时期单幅版画之中类似图像的关系,(2)它们与为纪念季节性节日而制作的,经常作为个人赠礼的“时节”类型绘画的连结,以及(3)它们与清初引进中国的欧洲“静物画”类型图像的联系。我的这项研究预计也将会呈现明末至清中叶的“静物画”版画作品中的图像组合,表现模式及蕴含意义之变化。

さち