Exhibitions

Paintings of the Immortal Poets:

Tales of Gods, People and Poetry

Waka poetry creates rich, beguiling worlds using just 31 syllables. It was a cornerstone of Japanese court culture and it also influenced a wide variety of visual artforms like calligraphy and painting.

It also inspired a genre known as ‘kasen-e.’ These are paintings of famous waka poets such as Kakinomoto no Hitomaro, a figure revered as ‘uta-no-hijiri,’ or ‘the great poet,’ and one of the main contributors to the Manyoshu, or Anthology of Ten Thousand Leaves, an ancient collection of waka poetry. Other examples include the Rokkasen, six famed poets mentioned in the introduction to the Kokin Wakashu poetry anthology, and the poets included in the Thirty-six Immortal Poets, an anthology compiled by Fujiwara no Kinto. From the late Heian period onwards, these portraits were often drawn alongside representative poems by each poet.

Kasen-e paintings flourished through Japan’s medieval period. During the Muromachi period, for instance, aspiring poets would often offer up these portraits to temples and shrines. Kasen-e enjoyed a new surge in popularity in Kyoto during the Edo period owing to a revival of courtly culture centered around the figure of the emperor. Many paintings adopted classical tropes used from the Heian period onwards, though new styles of portraiture also emerged. The warrior class were also fascinated by kasen-e as symbols of the power of Japanese culture from the Heian period onwards, a fascination evinced by kasen-e albums commissioned by the Tokugawa shogunate. As publishing took off during the mid-Edo period, many woodblock prints were produced based on the Immortal Poets. In this way, the poets and their poems became part of the cultural education of the Edo folk. They also become a popular theme of ukiyo-e. People would enjoy finding references to the poets in various mitate, a genre of ukiyo-e that contained allusions to famous stories and historical figures.

With a focus on the Edo period, this exhibition uses objects from Umi-Mori Art Museum’s collection to examine how the Immortal Poets were painted, mythologized and treasured in Japan. At times, the poets are meticulously drawn with adorable faces or depicted in a bold, exaggerated fashion. At other times, they are represented as famed Edo-period beauties, for instance. We hope you enjoy all these diverse portrayals of the Immortal Poets.

GENERAL INFORMATION

Hours: 10:00-17:00 (Last entry: 16:30)

Closed: Monday (except September 21st), and September 23rd

Admission: General admission: 1,000 yen, High school/university students: 500 yen, Junior high school students and younger: Free

*Admission is half price for people with disability certificates, etc. One accompany person is admitted free of charge.

*Groups of 20 or over will receive a discount of 200 yen per person.

Venue: Umi-Mori Art Museum (10701 Kamegaoka, Ohno, Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima)

With the support of: Hiroshima Board of Education and Hatsukaichi City Board of Education

Prologue: The Power of Waka Poetry and the Rise of the Immortal Poets

Waka poetry extolled the beauty of the four seasons and the subtleties of the human heart. It also served as a kind of prayer to the gods. Legends of Kitano Tenjin recounts the life of Sugawara Michizane, a talented poet who was later deified. This ancient text also contains stories about waka poetry and its relation to mysterious occurrences or expressions of divine providence. For people living during Japan’s Heian period, poetry was not just literature – it was imbued with divine power. This backdrop explains why poetry masters were venerated and deified back then. The first immortal poet to be depicted in paint was Kakinomoto no Hitomaro, a figure revered as ‘uta-no-hijiri,’ or ‘the great poet.’ He was portrayed in the form he took when he appeared in the dream of a Heian-period noble, with this image then becoming an object of worship. The prologue to this exhibition features works that illustrate the hidden spiritual power of waka poetry. It also explores the faith and devotion associated with this artform.

Color on paper

Kamakura-Nanbokucho period

Color on paper

Muromachi period, 16th century

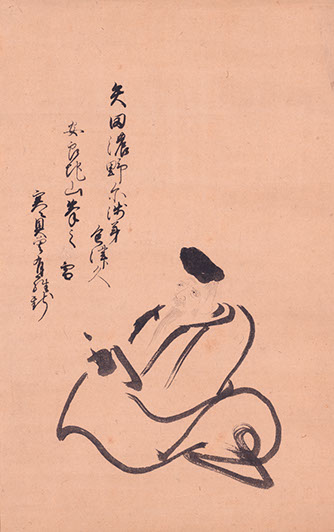

By Emperor Go-Yozei

Ink on paper

Edo period, 17th century

Chapter 1: The Lavish World of Kasen-e Paintings

The traditions of the Japanese court from the Heian period onwards were passed down through waka poetry and ‘kasen-e’, or paintings of famous waka poets. These artforms enjoyed a new surge in popularity in Kyoto in the 17th century, during the early Edo period, owing to a revival of courtly culture centered around Emperor Gomizuno-o. Kasen-e were also produced in volume in Edo (as Tokyo was formerly known) by painters from the Kano school, official painters for the shogunate. By commissioning, collecting and gifting these emblems of courtly culture, the warrior class imbibed this cultural authority and made it their own. Kasen-e often came in the form of small picture albums that were apparently used as gifts or bridal accoutrements during formal ceremonies held by shogunal or daimyo families. Many similar lavish items owned by feudal lords are still with us today, including shikishi poem cards and boxes for poetry fragments and kasen-e paintings. Furthermore, court nobles who penned prefaces and explanatory notes to poems were renowned as some of the finest writers of their day. This chapter explores the ornate world of Edo-period kasen-e paintings.

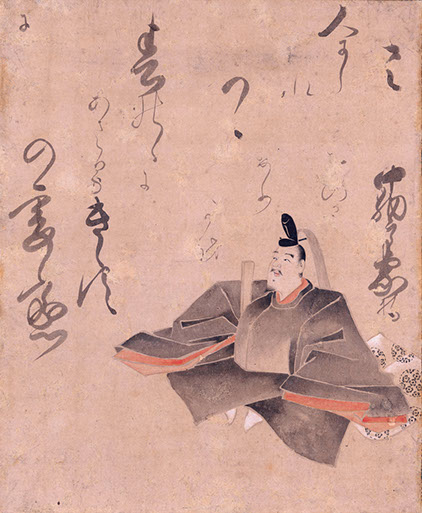

By the Iwasa school

Colorn on paper

Edo period, 17th century

Color on silk

Edo period, 17th century

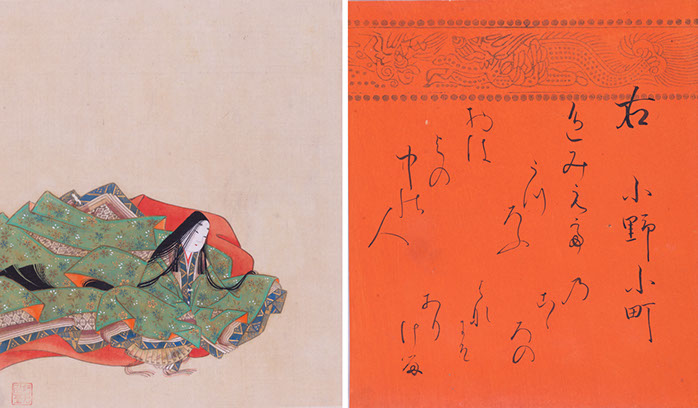

Chapter 2: The Lives and Loves of the Immortal Poets: Narihira and Komachi

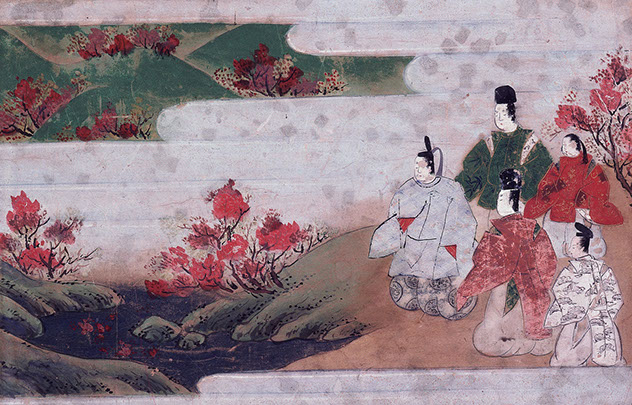

The lives of the Immortal Poets roused as much interest as their excellent poetry. These lives were full of romance and turmoil, as epitomized by the way the protagonist of the ancient Japanese classic The Tales of Ise was based on Ariwara no Narihira. Through their work, these poets fired up the imagination of many people and inspired numerous stories and paintings. In particular, people have long been captivated by Ariwara no Narihira and Ono no Komachi, a handsome man and beautiful woman who had many amorous encounters. Their lives and loves became mythologized when refracted through their poetry, just as celebrities are idolized and mythologized today. This chapter focuses on Ariwara no Narihira, the inspiration for the main character in The Tales of Ise, and Ono no Komachi, the archetype of a fallen beauty. It explores the relation between their poetry, their portrayals, and the stories they inspired.

2 albums Color on paper

Edo period, 17th century

By Suzuki Harunobu

Medium-sized nishiki-e

Ca. 1766-68 (Meiwa 3-5)

Chapter 3: The Immortal Poets and Ukiyo-e: Cultural Education and Playful Parodies

During the Edo period, The Thirty-six Immortal Poets and One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets were widely read as illustrated woodblock-print books, with the poems and tales about their authors becoming an indispensable part of cultural education at that time. As discussed in Chapter 2, people were captivated by the verses and lives of the Immortal Poets. This interest led to the production of many illustrated books filled with poems, portraits, biographies, and episodes from the lives of the poets. Ukiyo-e prints also began to feature depictions of contemporary beauties and actors that playfully alluded to the Immortal Poets. In this way, the poets lived on in the cultural education and witty playfulness of the Edo folk.

By Suzuki Harunobu

Medium-sized nishiki-e

Ca. 1768-69 (Meiwa 5-6)

By Utagawa Toyokuni III (Utagawa Kunisada)

Large nishiki-e

1852 (Kaei 5)