Exhibitions

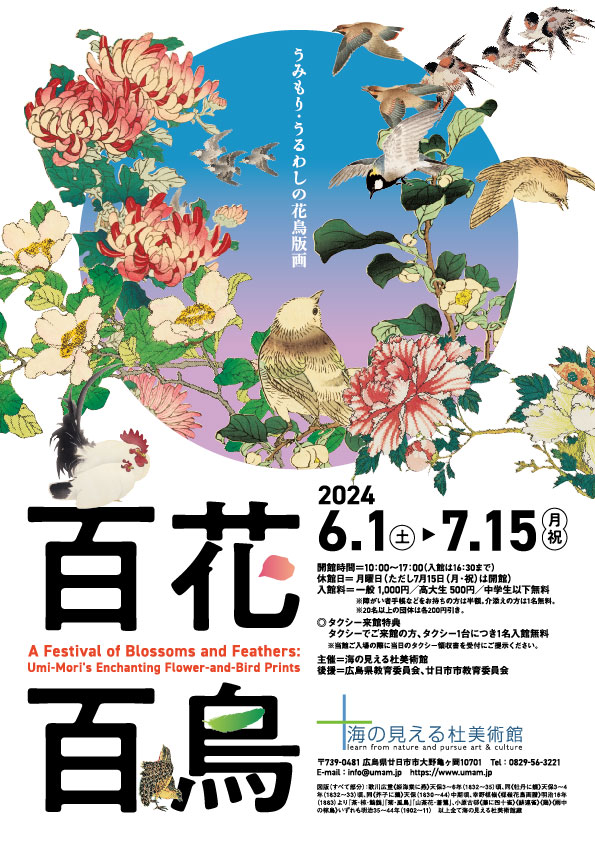

A Festival of Blossoms and Feathers: Umi-Mori’s Enchanting Flower-and-Bird Prints

When ukiyo-e works first emerged during the early-modern era, they primarily depicted beauties and famous actors, for example. Around the middle of the 19th century, though, woodblock prints also began to portray flowers and birds, with the genre developing in a variety of directions thereafter. Flower-and-bird paintings depicting seasonal flowering plants, birds, insects and fish have occupied an important place in Japanese art since ancient times.

During the Edo period (1603–1868), numerous Ming- and Qing-period Chinese picture albums were brought over to Japan. Featuring paintings and treatises on art theory, these albums had a major influence on Japanese art, including ukiyo-e. Flower-and-bird prints were no exception, with the genre growing in leaps and bounds while incorporating the discoveries of natural history, botany and other practical sciences that were undergoing a boom back then. The highly-accomplished flower-and-bird pictures of the ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) were particularly popular. Hiroshige was a prolific artist and his works came to typify the Edo-period flower-and-bird genre, with his pictures having a huge impact of later works too.

In the Meiji era (1868–1912), Kono Bairei (1844–95) created works that served new roles in addition to art appreciation. A leading figure in Kyoto painting circles, Bairei produced numerous painting manuals for art education purposes, for instance, as well as design books to assist the production of various crafts for export. A new path for modern flower-and-bird prints was also opened by Ohara Koson (1877–1945), an artist whole expressive style marked a clear departure from traditional flower-and bid works, as epitomized by Hiroshige’s oeuvre. From the off, Koson produced for foreign markets and his works were very popular in the West.

This exhibition introduces Umi-Mori Art Museum’s collection of flower-and-bird prints, with a focus on ukiyo-e pictures, picture albums and painting manuals from the early-modern to modern era. The exhibition introduces Hiroshige’s representative Edo-period prints, Bairei’s numerous picture albums, and the modern works of Koson, that master of Meiji- and Showa-era flower-and-bird prints. These are displayed alongside various picture albums from each era. We hope you enjoy this voyage through the beautiful seasonal world of flower-and-bird prints.

General Information

Hours: 10:00-17:00 (Last entry: 16:30)

Closed: Monday (except July 15th)

Admission: General admission: 1,000 yen, High school/university students: 500 yen, Junior high school students and younger: Free

*Admission is half price for people with disability certificates, etc. One accompany person is admitted free of charge.

*Groups of 20 or over will receive a discount of 200 yen per person.

Venue: Umi-Mori Art Museum (10701 Kamegaoka, Ohno, Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima)

With the support of: Hiroshima Board of Education and Hatsukaichi City Board of Education

Chapter 1: The first stirrings of Edo-period flower-and-bird prints: The influence of Chinese picture albums and Japanese woodblock print books

When ukiyo-e works first emerged during the early-modern era, they primarily depicted beauties and famous actors, for example. However, flowers and birds also became a prominent theme from around the middle of the 19th century. This chapter primarily features earlier flower-and-bird pictures that appeared in woodblock-printed books.

At that start of the Edo period (1603–1868), many Chinese picture albums were brought over to Japan. Featuring paintings and treatises on art theory, these albums had a major influence on Japanese art, including ukiyo-e. One particular bestseller was the Mustard Seed Garden Painting Manual. This work was published by Li Yu (1611–ca. 1680), a novelist active from the end of the Ming period to the start of the Qing period, with pictures drawn by Wang Gai (dates unknown), a painter active at the start of the Qing period. The book was imported in volume from China, with many woodblock-print versions also published in Japan. Before then, picture albums had only had a limited distribution in Japan, but the popularity of these Chinese works changed everything, with these albums now reaching the eyes of many more people.

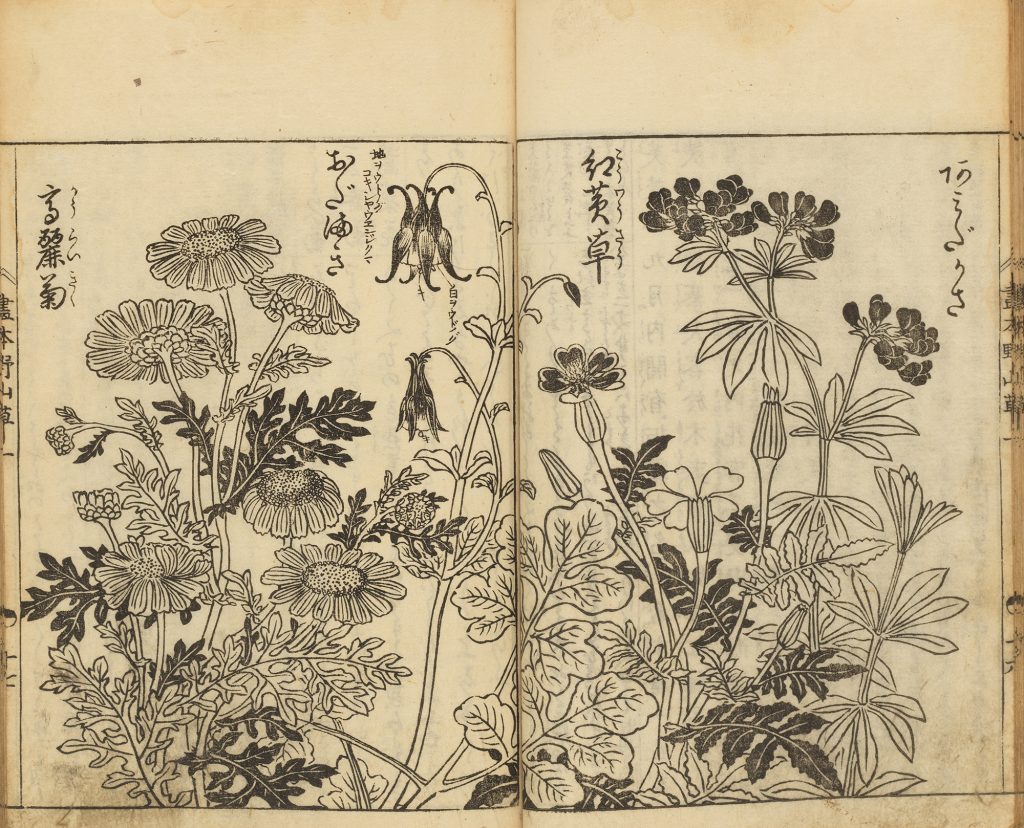

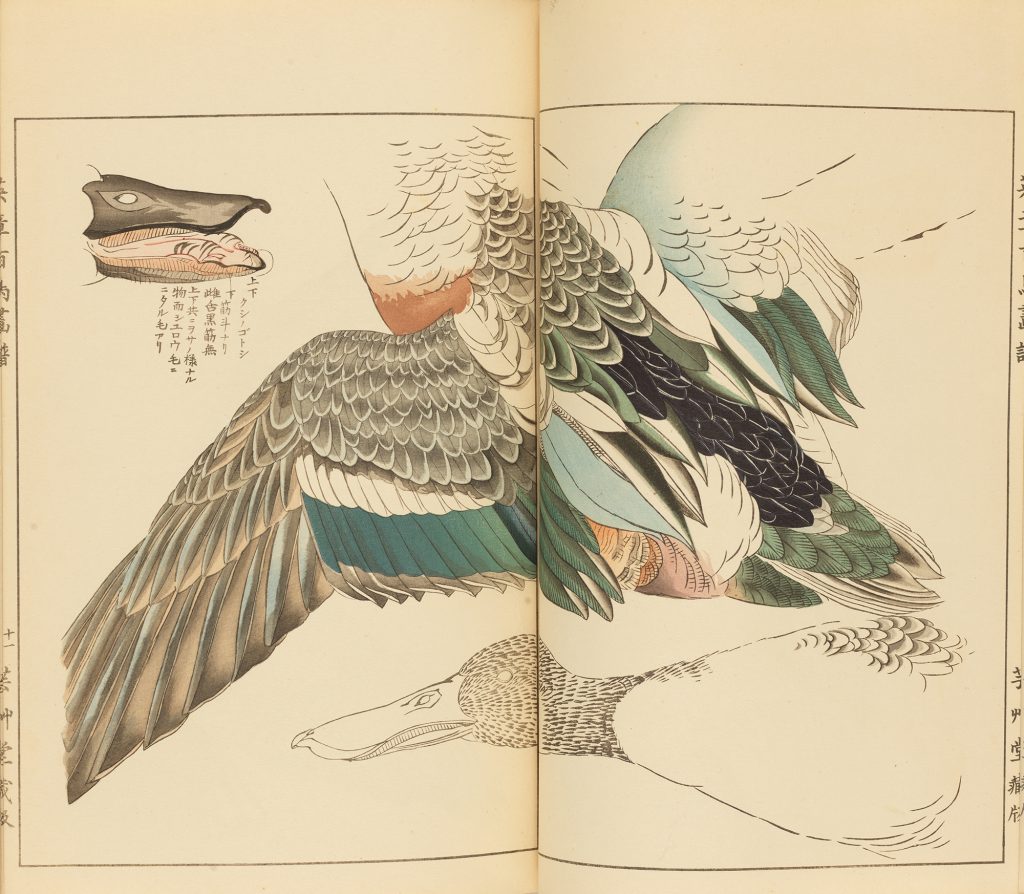

In the mid-Edo period, illustrated natural history books were produced throughout Japan as more people began to study herbalism at the urging of the eighth shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune. This led to the creation of picture albums based on painstaking observation and meticulous sketching, including Ehon Noyamagusa (Illustrated Field and Mountain Plants) by the Osaka painter Tachibana Yasukuni (1715–1792), and Kacho Shashin Zui (Lifelike Illustrations of Birds and Flowers), a representative picture book by the ukiyo-e artist Kitao Shigemasa (1739–1820).

Chapter 2: Hiroshige’s flower-and-bird prints: The emergence of the flower-and-bird ukiyo-e genre

Umi-Mori Art Museum began collecting flower-and-bird prints by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) around 30 years ago and we now have the largest such collection in Japan.

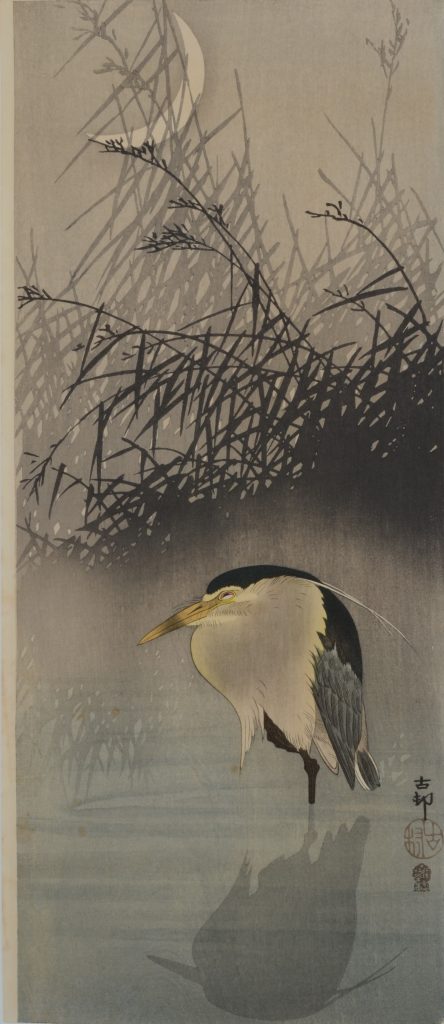

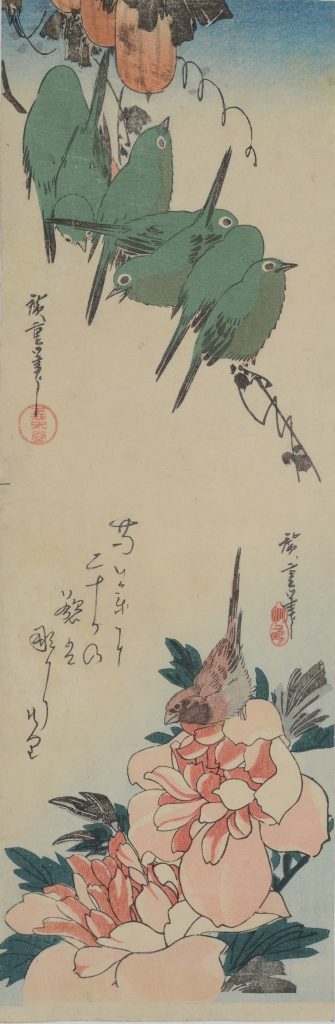

The ukiyo-e flower-and-print genre was established in the early Tenpo era (1830–44) by Hiroshige. His prints came in the long, thin tanzakugata format or a small-sized format, with these elegant works featuring pictures of seasonal flowering plants and various birds adorned with Chinese poems or other forms of poetry. Around 600 of these are still with us today, with Hiroshige accounting for almost all the flower-and-bird prints created from the Tenpo era to around the Kaei era (1848–55). During the first half of the Tenpo era, Hiroshige also produced Every Variety of Fish, a series portraying fish and shellfish with flowering plants and vegetables of the four seasons. Originally made exclusively for the Kyokashi, a guild of comic tanka poets, the series was later sold to the general public too.

With their small sizes and affordable prices, Hiroshige’s flower-and-bird prints were mass-produced and enjoyed by many ordinary folk. Like the hanging scrolls hung in tokonoma alcoves, they probably brought a sense of seasonality to everyday lives. In name and reality, Hiroshige’s works came to typify the Edo-period flower-and-bird genre, with his pictures also having a huge impact of later works.

Chapter 3: Kono Bairei’s legacy: The flower-and-bird albums produced by a titan of Kyoto painting circles

Kono Bairei (1844–95) studied under the Shijo school painter Shiokawa Bunrin (1808–1877). After Bunrin’s death, Bairei became a central figure and driving force in Kyoto’s modern painting circles. As well as being a successful painter, Bairei was also passionate about nurturing younger artists, and he helped to establish Kyoto Prefectural Art School and the Kyoto Art Association. Many of his pupils became prominent painters of the next generation, including Takeuchi Seiho and Kikuchi Hobun.

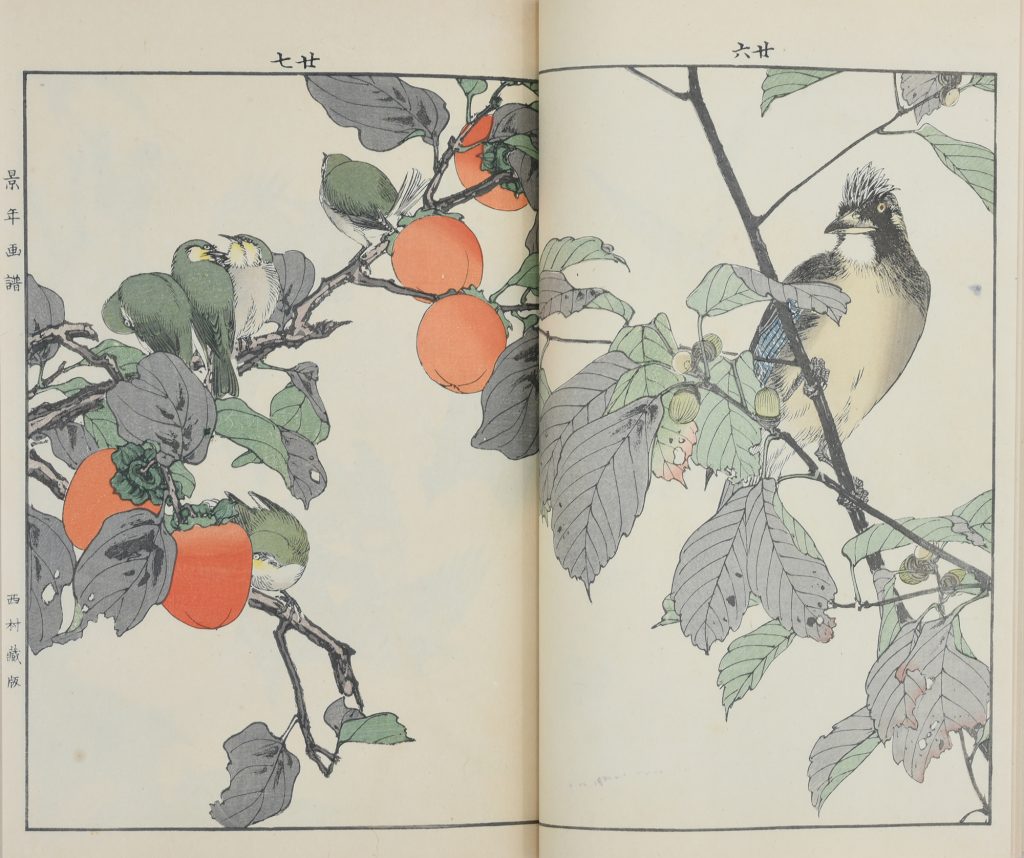

At his own private cram school, Bairei supervised the production of numerous painting albums that would serve as painting manuals. He also wielded the brush himself and was particularly adept at flower-and-bird pictures, with this talent leading to the creation of many flower-and-bird picture albums. The Meiji 20s and 30s (1887–1906) were a boom time for flower-and-picture albums, with Bairei particularly prolific. Among the many albums he produced around this time were Bairei Hyakucho Gafu (Bairei’s Album of One Hundred Birds), an 1882 work that received a certificate of merit for painting at the 1st Domestic Competitive Painting Exhibition; 1886’s Bairei Gafu (Bairei’s Painting Album); and 1889’s Ehon Inaka no Tsuki (Illustrated Book of the Moon on the 20th Night of the Month). The publication of these works can also be counted among Bairei’s achievements in the field of painting education. Another illuminating example is Bairei Kacho Gafu (Bairei’s Album of Flowers and Birds). This was originally printed in 1883 as a series of single-sheet multicolor woodblock prints. After Bairei’s death, though, the prints were compiled together and published as a handy woodblock-printed book, with this chain of events speaking volumes about the strong demand for Bairei’s flower-and-bird albums.

Chapter 4: The development of modern flower-and-bird prints: The role required of picture albums

Flower-and-bird pictures remained a major theme of woodblock prints from the Meiji era (1868–1912) onwards, with a variety of picture albums produced alongside works influenced by Western art. The new Meiji government pursued a policy of shokusan-kogyo (“nurturing new industries”). This led to a clamor for flower-and-bird paintings to decorate ceramics, textiles and other crafts earmarked for export. This is turn led to a brisk demand for design books with compositions and patterns that artisans could reference, with publishers subsequently issuing a diverse range of painting albums and manuals.

One representative example is Keinen Kacho Gafu (Keinen’s Album of Flowers and Birds), which was published in 1891 by Nishimura Sozaemon, the 12th generation head of the Chiso family of Kyo yuzen dyers. This work illustrates the role played by this new generation of flower-and-bird albums, with Nishimura declaring it would assist all kinds of art production, not just textiles like yuzen-zome. The book was revised by a naturalist and it was characterized by detailed lifelike depictions based on the natural sciences. It was followed by numerous picture albums containing realistic depictions of flower and bird habitats based on the discoveries of practical sciences. Other examples include Eisho Hyakucho Gafu (Eisho’s Album of Flowers and Birds), a type of illustrated natural history book that was advertised as “a major reference book for artists and craftsmen”; and Seiyo Soka Zufu (Picture Album of Western Plants), a resplendent work mainly themed around Western flowers.

Chapter 5: Ohara Koson’s flower-and-bird prints: Seasonal sentiments and the vitality of life

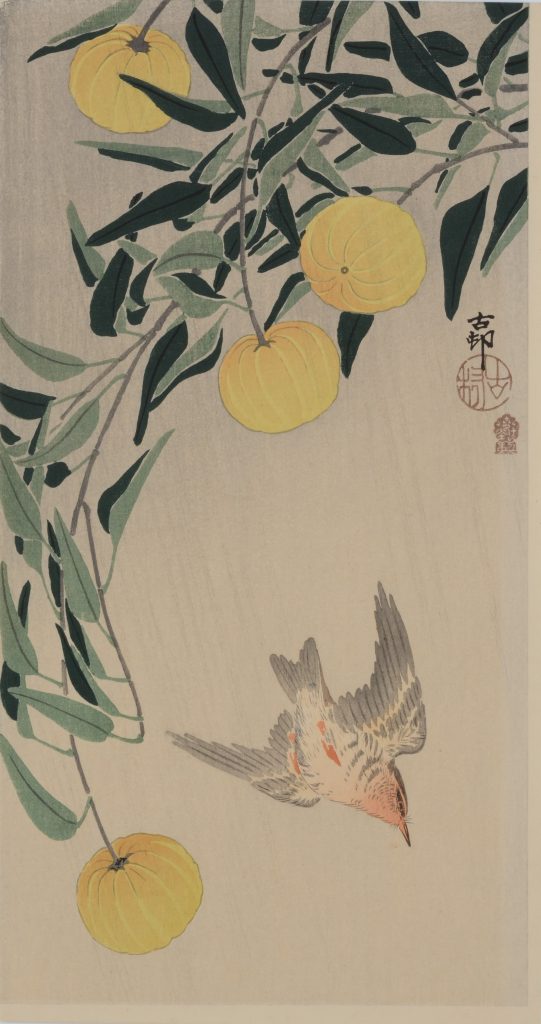

The painter Ohara Koson (1877–1945) was active from the late 19th century to the early 20th century. His works were mainly popular with Western audiences, though he has recently garnered more attention in Japan too through research projects and exhibitions.

In the Meiji 20s and 30s (1887–1906), Koson studied under the Japanese painter Suzuki Kason and he predominately worked on flower-and-bird paintings. A series of sumptuous flower-and-bird picture albums by artists like Kono Bairei, Watanabe Seitei, and Imao Keinen were released around the time Koson was learning his craft, with these probably influencing the formation of Koson’s own painting style and the direction of his artistic pursuits.

In 1903, the 27-year-old Koson stopped producing Japanese-style paintings. Instead, he worked on the production of flower-and-bird prints for foreign customers. These were published by Akiyama Buemon and Matsuki Heikichi, two publishers who had shifted the base of their activities to woodblock prints. Koson skillfully utilized traditional techniques such as atenashi bokashi (whereby pigments are daubed on a flat, uncarved woodblock surface to create an indeterminate shading effect) and musenzuri (whereby shapes are formed from planes of color, without using any outlines) to produce vibrant, tranquil scenes that could easily be mistaken for hand-drawn works. He even used subtle gradations of color to represent seasonal, temporal and atmospheric changes, with his flower-and bird pictures rich in poetic sentiment.