Exhibitions

Hikifuda: Auspicious Handbills Celebrating the New Year PartⅡ

Welcome to the exhibition Hikifuda: Auspicious Handbills Celebrating the New Year Part II. Hikifuda are printed handbills that merchants would hand out to customers as a form of greeting. During the New Year period in particular, store’s would distribute handbills adorned with auspicious motifs and the store name. Umi-Mori Art Museum’s collection includes over 2,000 handbills dating from the Meiji era to the Taisho era.

The first Hikifuda: Auspicious Handbills Celebrating the New Year exhibition was held in 2021. Part II delves into this world once more to bring us a new selection of handbills, including some never exhibited before.

The exhibition is divided into five chapters themed around handbills with calendars from the early- to mid-Meiji era, handbills with traditional motifs, auspicious handbills incorporating aspects of modern culture, handbills with scenes of war, and handbills with pictures of women, for example.

Hikifuda were first produced in the Edo period (1603–1868) using woodblock prints. A new era of mass production began in the mid-Meiji era with the arrival of new technologies like copper plates, lithographic prints and machine printing. By the end of the Meiji era, over 10 million handbills were being distributed each year, a figure surpassing the number of households in Japan.

These handbills feature a rich array of imagery. Some use traditional auspicious motifs like treasures ships or the deities Ebisu and Daikoku, for example, while others portray contemporary events, customs or fashions. The handbills extol urban culture while also revealing how advertising and communication worked in this bygone age. In this sense, hikifuda serve not only as examples of popular culture but also as important historical and ethnological materials.

Please enjoy this voyage into the colorful and humorous world of hikifuda handbills. We hope the exhibition conveys the sense of excitement people felt back then as the festive season approached amid prayers for business success, prosperity and harmonious households.

General Information

Hours: 10:00-17:00 (Last entry: 16:30)

Closed: Monday, and November 11th

Admission: General admission: 1,000 yen, High school/university students: 500 yen, Junior high school students and younger: Free

*Admission is half price for people with disability certificates, etc. One accompany person is admitted free of charge.

*Groups of 20 or over will receive a discount of 200 yen per person.

Venue: Umi-Mori Art Museum (10701 Kamegaoka, Ohno, Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima)

With the support of: Hiroshima Board of Education and Hatsukaichi City Board of Education

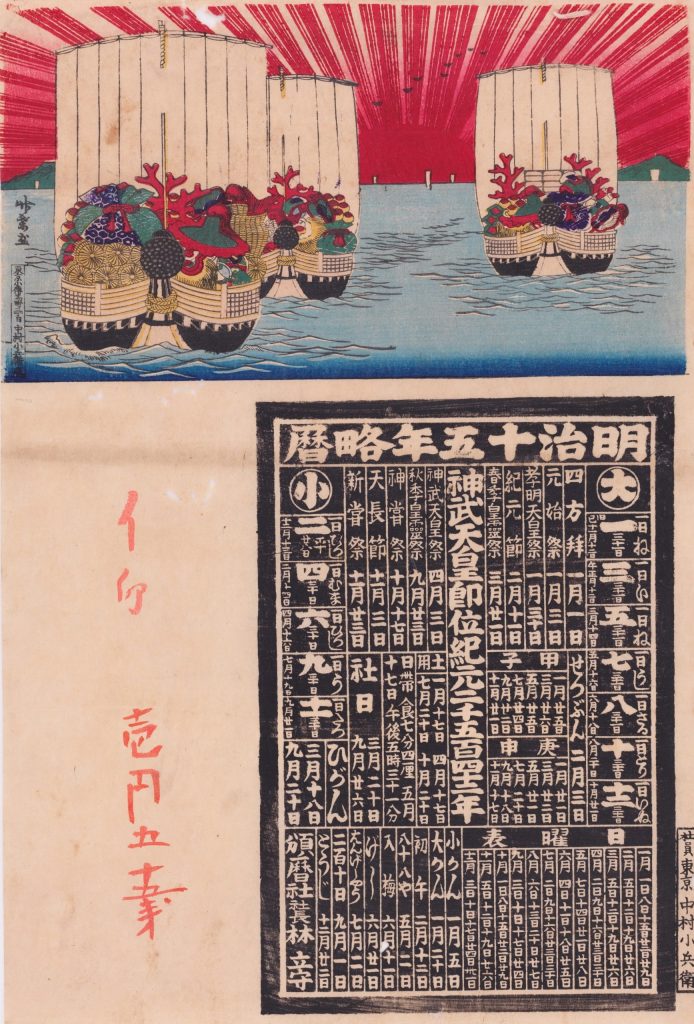

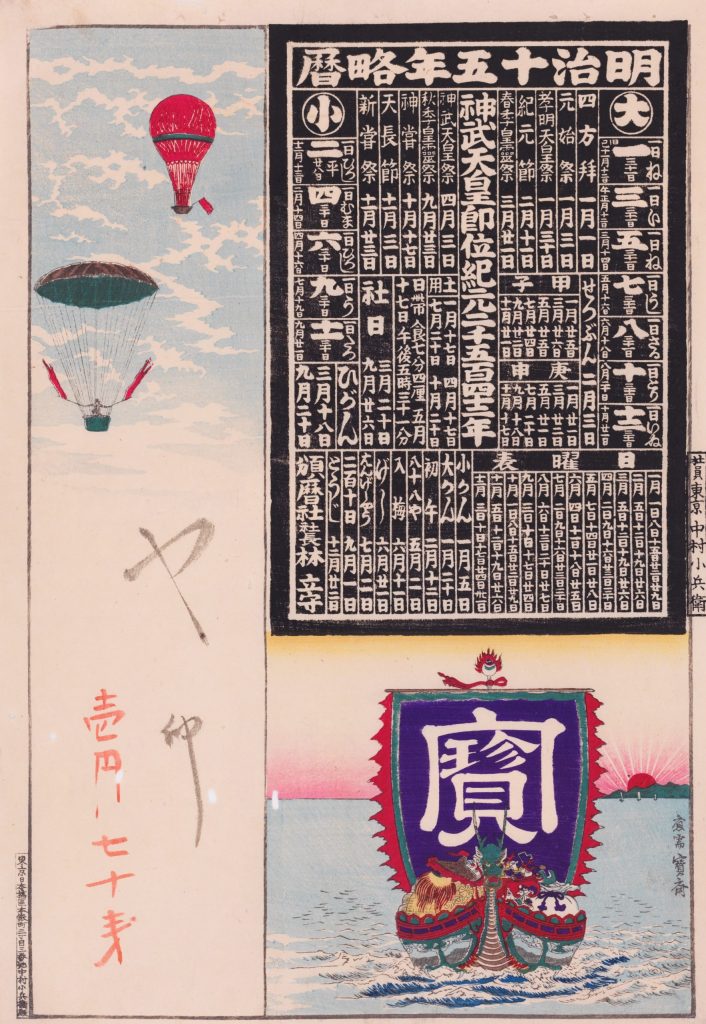

Chapter 1. On the Eve of a Golden Age

At the start of the Meiji era, hikifuda handbills were mainly produced by calendar wholesalers, a group with official permission to print calendars. Many printing firms entered the handbill business after calendar production was liberalized in 1883 (Meiji 16). These firms battled it out using new technologies like copper and lithographic prints. Machine printing ushered in a new age of mass production, with handbills then distributed across Japan. This chapter features the kind of simple, homespun handbills produced up until 1887 (Meiji 20).

Chapter 2. The Golden Age of Hikifuda Handbills

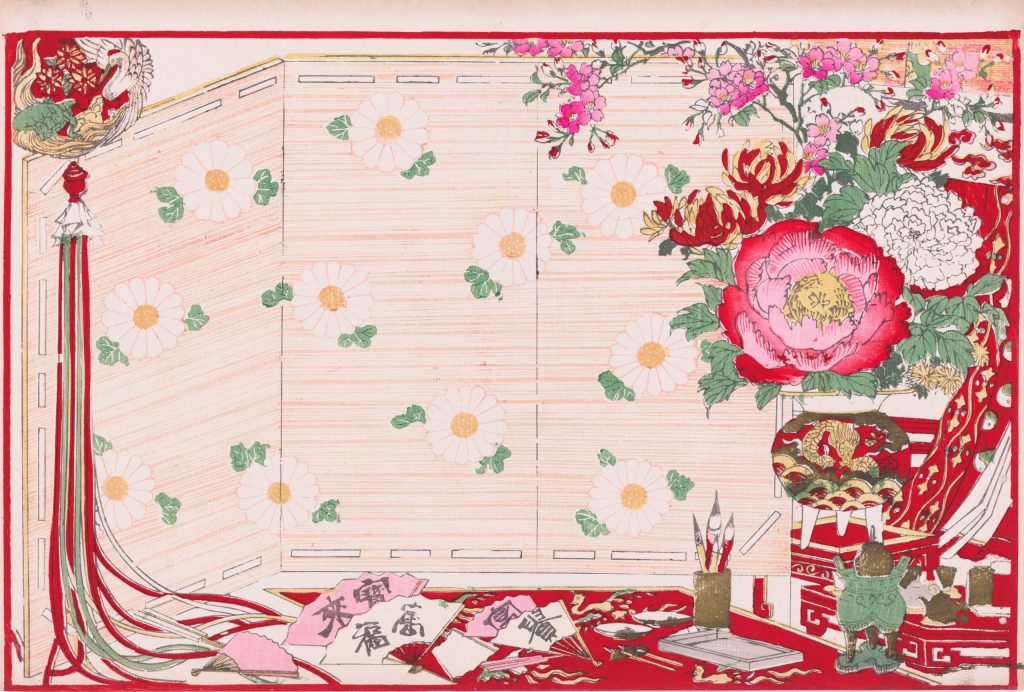

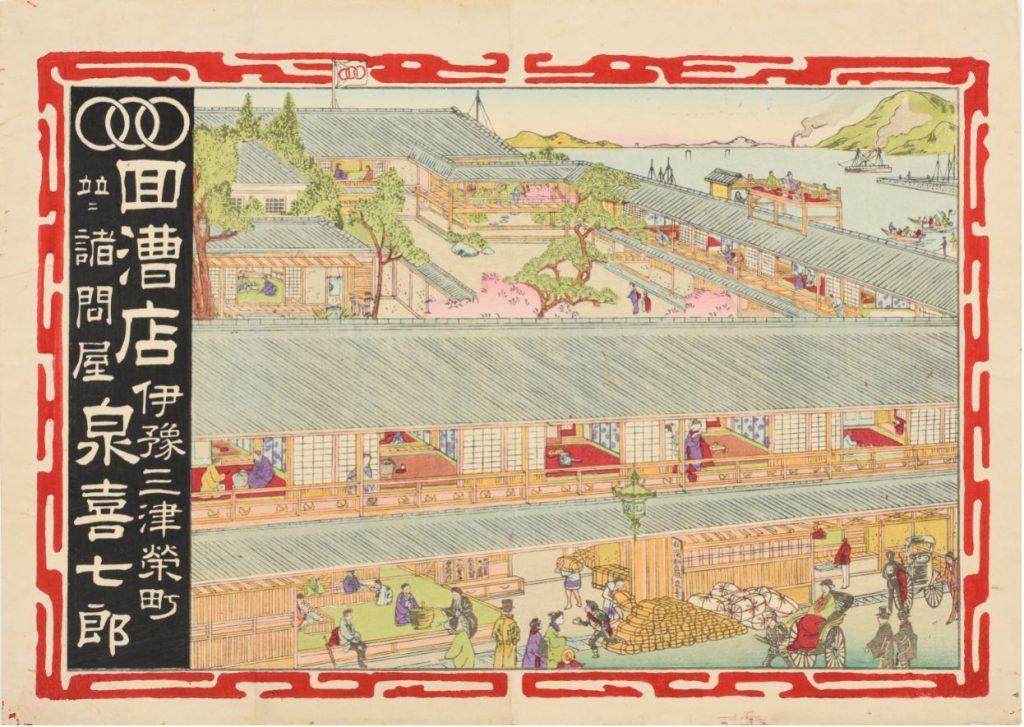

Umi-Mori Art Museum’s collection includes many handbills with no store or company names. These are samples shown by printing firms to prospective clients. After a merchant chose a sample they liked, the store name would be printed on top, with the finished handbills then distributed to customers as a form of greeting at the year’s end. Handbills were used to advertise stores and create a sense of familiarity and trust among customers.

Hikifuda usually feature auspicious motifs suitable for any kind of business, such as cranes, turtles, or the deities Ebisu and Daikoku. However, handbills were also customized to meet client wishes. Tea store handbills would feature scenes of tea picking and liquor store handbills scenes of liquor production, for example. There are even examples of bespoke handbills featuring images of a particular store.

Handbills produced from the mid- to late-Meiji era reflected the spirit of the times. They reveal how important customer relations were for business back then.

Chapter 3. Auspicious Motifs for a Modern Age

Printing firms produced a wide-range of hikifuda with eye-catching images designed to meet the varied demands of their clients.

As Japan modernized, printing studios and artists moved with the times. While not forgoing traditional motifs, they enthusiastically incorporated aspects of the new culture, such as trains, planes, telephones, and the latest fashions. These novel, unconventional images piqued the public’s interest. With their promise of wealth, comfort and convenience, they served as auspicious motifs for a modern age.

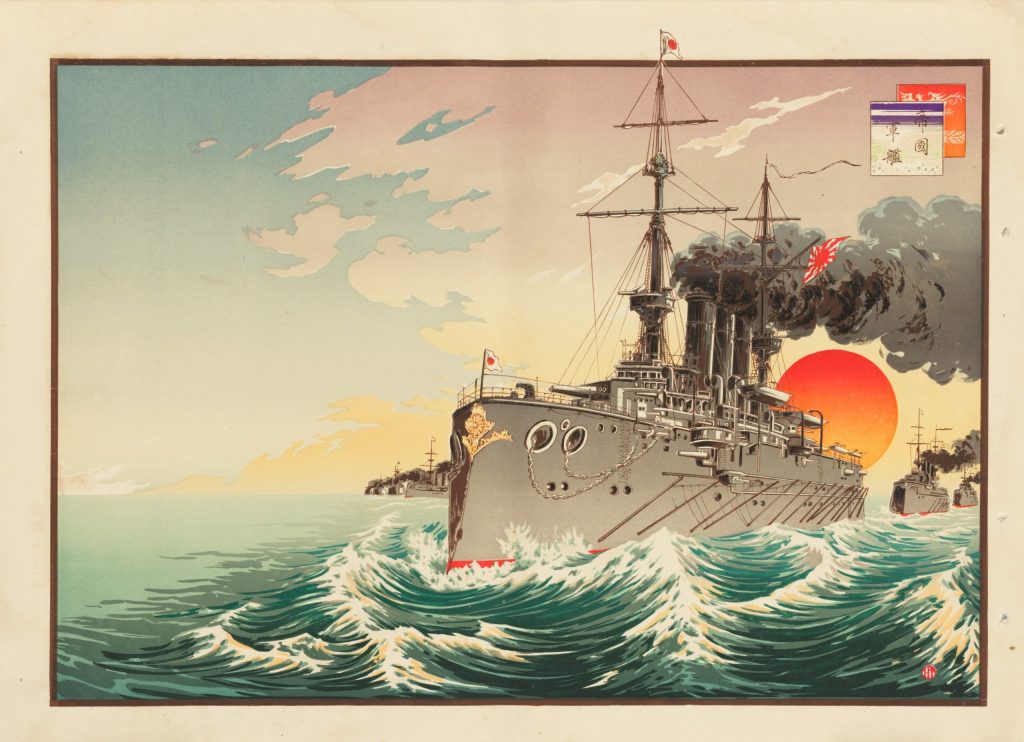

Chapter 4. Hikifuda and Images of War

Japan experienced two wars during the era of hikifuda production: The Sino-Japanese War of 1894 (Meiji 27) and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 (Meiji 37). As such, handbills also featured motifs related to war, such as battleships, departing troops, fighting soldiers, and joyous people celebrating victory.

For contemporary Japanese, these victories were a sign of Japan’s rapid development and growing prosperity. Images of valiant, distinguished soldiers symbolized Japan’s accession to great-power status alongside the Western nations. The distribution of these images among the wider public was another aspect of Japan’s modernization process.

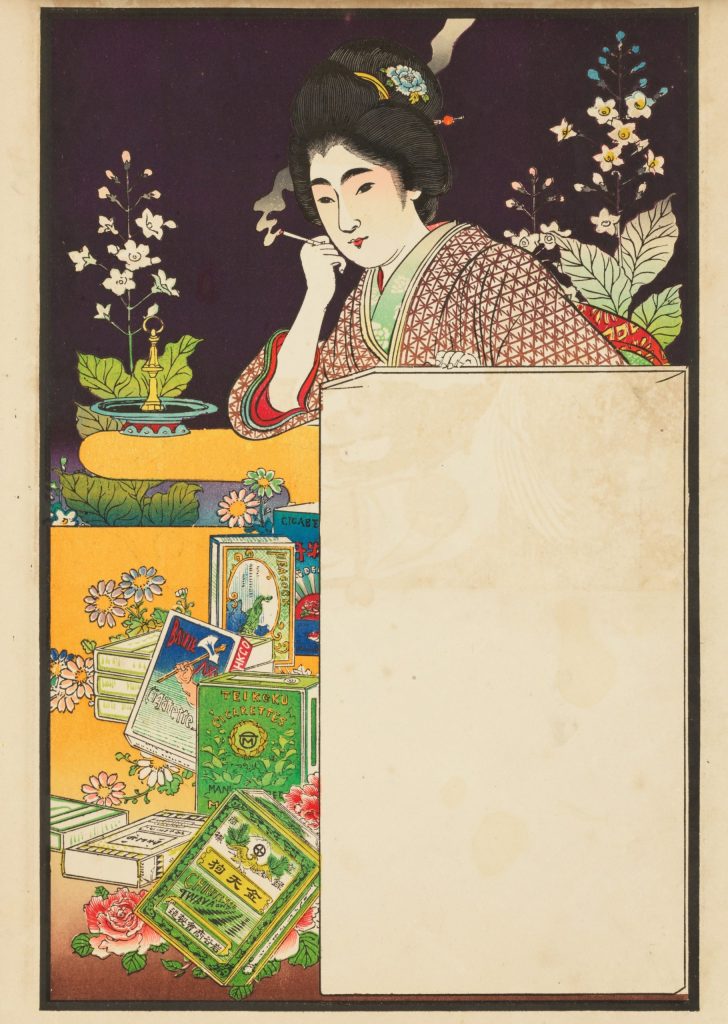

Chapter 5. Hikifuda and Depictions of Women

Hikifuda often feature depictions of women. Some handbills portray women buying clothes and so on at stores or dressed gorgeously in the latest fashions of the day. Other handbills show upper class ladies behaving gracefully at home. By conveying the idea that beauty was obtainable through shopping, these images helped to entice people to stores. They also served as auspicious motifs symbolizing prosperous, happy households.

Images of women became more elaborate and realistic during the Taisho era with the emergence of chromolithography. These images had little correlation with the actual goods sold in stores. Instead, they focused on the appreciation of the women themselves, with handbills becoming more like advertising posters. The golden age of hikifuda drew to an end from the Taisho era, but handbills still survived by mimicking the posters of beautiful wome n already in use at department stores and so on.