Exhibitions

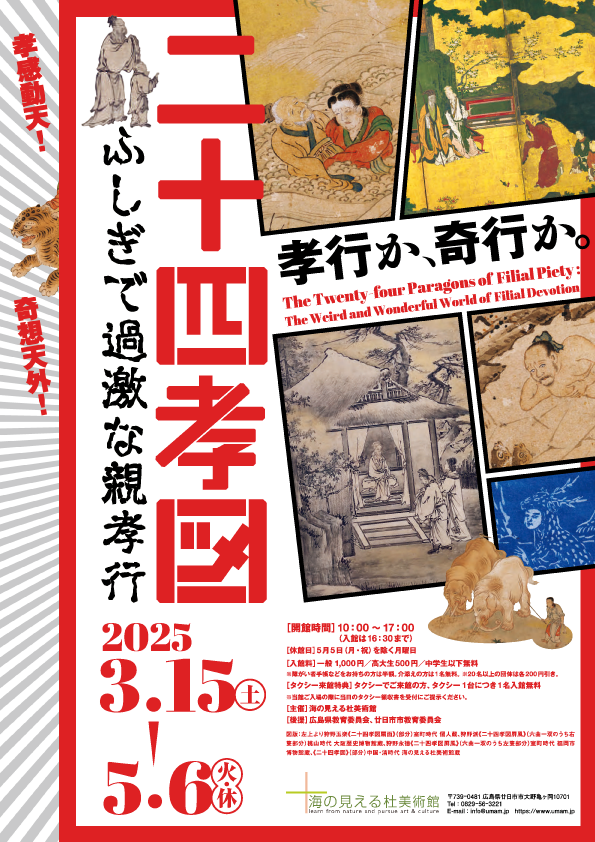

The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety: The Weird and Wonderful World of Filial Devotion

Introduction

Centered around China and East Asia, the world of Confucianism abounded with fables of devoted children performing their filial duties. From ancient times, these stories were depicted pictorially in Eastern Han tombs and mausoleums, for example. In this way, numerous tales of filial children were passed down through the ages. These included The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety, a selection of 24 episodes first compiled in the Dunhuang manuscripts, which date from the end of the Tang era to the Five Dynasties period. The line-up of The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety was not fixed, with selections changing according to source texts, for instance. Though sometimes extreme, these stories permeated into people’s beliefs and lifestyles.

From the Muromachi period (1392–1573), paintings and images of The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety spread throughout Japan following the import of illustrated books like Twenty-four Illustrated Verses of Filial Piety by the Yuan-dynasty literati figure Guo Jujing (?–1354). There are hardly any extant examples of these medieval works that arrived from China or the Korean Peninsula, but Japan still has several masterful screen-and-wall paintings and fan pictures by the Kano school, Japan’s leading painting school from the Muromachi period to the Momoyama period (1573–1603).

This exhibition is the first to examine the reception and evolution of Japanese paintings of The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety. In the past, these were solely regarded as kankaiga, or “admonition pictures” intended to convey Confucian ideas. However, pictures of The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety have also served to honor and memorialize deceased parents. The exhibition explores this rarely-seen facet using paintings by the Kano school and others.

Finally, we would like to express our deepest gratitude to those who loaned their valuable artworks and to everyone whose cooperation made this exhibition possible.

General Information

Hours: 10:00-17:00 (Last entry: 16:30)

Closed: Monday (except May 5th)

Admission: General admission: 1,000 yen, High school/university students: 500 yen, Junior high school students and younger: Free

*Admission is half price for people with disability certificates, etc. One accompany person is admitted free of charge.

*Groups of 20 or over will receive a discount of 200 yen per person.

Venue: Umi-Mori Art Museum (10701 Kamegaoka, Ohno, Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima)

With the support of: Hiroshima Board of Education and Hatsukaichi City Board of Education

Chapter One

The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety: Depictions of Filial Children in East Asia

Chinese Confucianism places great importance on “filial piety” and devotion to one’s parents. Stories about dutiful offspring first emerged long ago. These tales spread across East Asia and were widely shared among the Japanese nobility from ancient times too. Some of these filial children were grouped together as The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety, though the members were not fixed and the story contents also varied. Pictures of The Twenty-four Paragons were promulgated in woodblock-printed books produced in China and the Korea Peninsula in the 14th century, with these having a major influence in Japan too. Images of The Twenty-four Paragons subsequently spread throughout Japan, as revealed by extant paintings by the Kano school and others from the late-Muromachi period to the Momoyama period.

The first half of Chapter One introduces The Twenty-four Paragons through Kano Gyokuraku’s Fan Paintings of The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety, a set of 24 pictures depicting episodes involving each dutiful child, and The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety (The University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts). This occasion marks the first time either of these precious works from the late-Muromachi period has featured in an exhibition. a set of 24 sheets and 2 sheets for foreword.

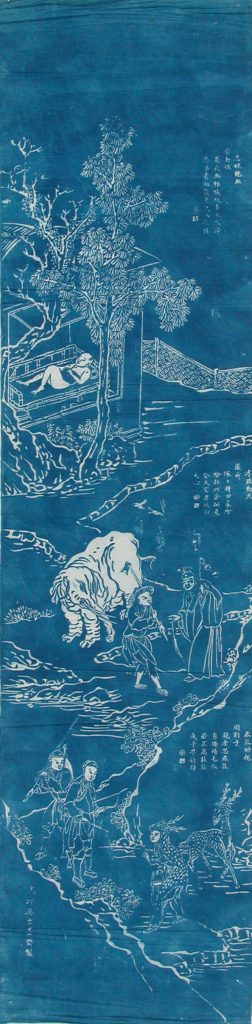

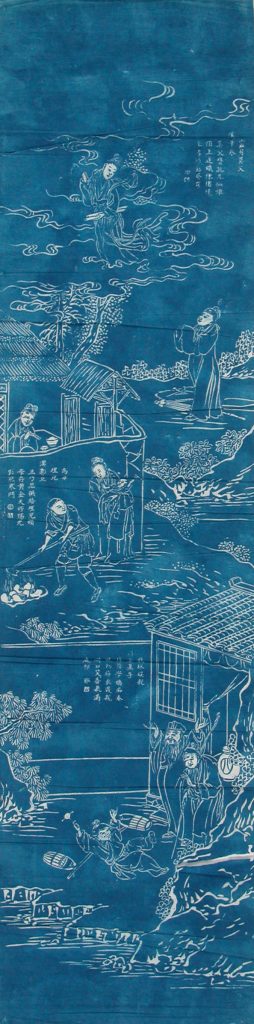

The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety, as Seen by Ordinary Folk

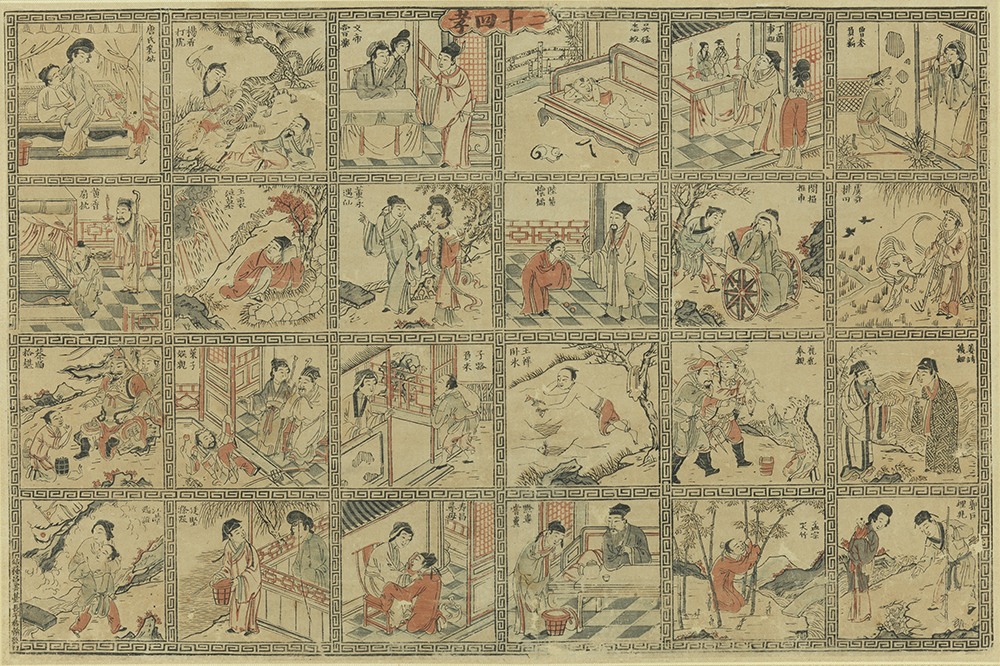

The second half of Chapter One explores the dissemination of images of The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety among ordinary people in China and Japan. This dissemination was propelled by a diverse range of woodblock prints and printed books. Unfortunately, hardly any medieval works of this type still exist in China. However, our museum has a collection of Suzhou prints produced in and around the city of Suzhou from the Qing dynasty onwards. This collection includes some extremely precious early-modern depictions of The Twenty-four Paragons from the 17th century. These reveal how filial devotion fermented a fervent folk belief in ancestor worship in China. While emphasizing the importance of memorial services for deceased parents, these works also contain earthly prayers for the familial prosperity of the filial children performing these services.

During the Edo period (1603–1868), woodblock-printed books with illustrations were produced in volume in Japan. These served as textbooks for the general public and children, for example, or as texts containing admonitions. These images of The Twenty Four Paragons were also promulgated widely among ordinary folk in the form of ukiyo-e. This section introduced some unconventional depictions of The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861).

Chapter Two

Diverse Depictions of The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety

This chapter features some masterful paintings of The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety by the Kano school, Japan’s leading painting school from the Muromachi period to the Momoyama period. These include the Tochigi Prefectural Museum Version, one of the earliest extant examples of a large-scale depiction, and the Fukuoka City Museum Version, a mid-16th-century work that portrays the filial children amid picturesque landscapes. With their expansive portrayals of several Paragons, meanwhile, the Rakutouihoukan Version and the Osaka Museum of History Version recall the grandeur of the Momoyama period.

An examination of the reception of The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety paintings from medieval times onwards points to the role they played in mourning deceased parents or praying for the repose of ancestral souls. Filial piety was also highly valued when belief in the Ten Kings of Hell flourished from the Kamakura period (1192–1333) onwards, with two filial children featuring alongside depictions of the Ten Kings in Illustrated Anthology of Writings on Praising the Ten Kings of Hell and Accumulating Good Deeds, for instance.

The aforementioned Fukuoka City Museum Version and Rakutouihoukan Version were also used in memorial services. By setting up these folding screen paintings of The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety during services, bereaved family members could liken themselves to the Twenty-four Paragons while also offering up prayers for familial prosperity and encouraging the next generation of children to show filial piety.

Related Exhibition

Depictions of The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety in Chinese Woodblock Prints

Hardly any research has been undertaken into Chinese woodblock-print depictions of The Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety. However, this genre has a history spanning around 350 years, from Suzhou prints dating back to reign of the Qing dynasty’s Kangxi Emperor (1662–1722) to New Year pictures from the 20th century.

Our museum has a collection of 74 Qing-period woodblock prints encompassing 23 different genres. This accounts for over half the world’s confirmed total at this moment in time. This exhibition provides a comprehensive overview of this collection.

At first glance, three lineages can be discerned within these works, namely Records of Filial Piety, Twenty-four Illustrated Verses of Filial Piety, and Important Stories of the Past to be Recorded and Remembered Daily. However, the latter lineage seems most prominent when it comes to the woodblock print depictions. As with paintings, these prints were a way to enlighten and admonish the viewer while memorializing and showing respect for the deceased. They also served as auspicious motifs that fused Daoist and folk beliefs, for example, or as “pure offerings” that were prized within literati culture. We hope this exhibition can prompt a variety of “discoveries” that lead to new research in this area.